Who Listens to the Fed?

In our working paper Speaking of Inflation: The Influence of Fed Speeches on Expectations, that is writen together with Eleonora Granziera, Greta Meggiorini, and Leonardo Melosi, we show that Federal Reserve communication is not interpreted uniformly across audiences. The paper can be downloaded here:

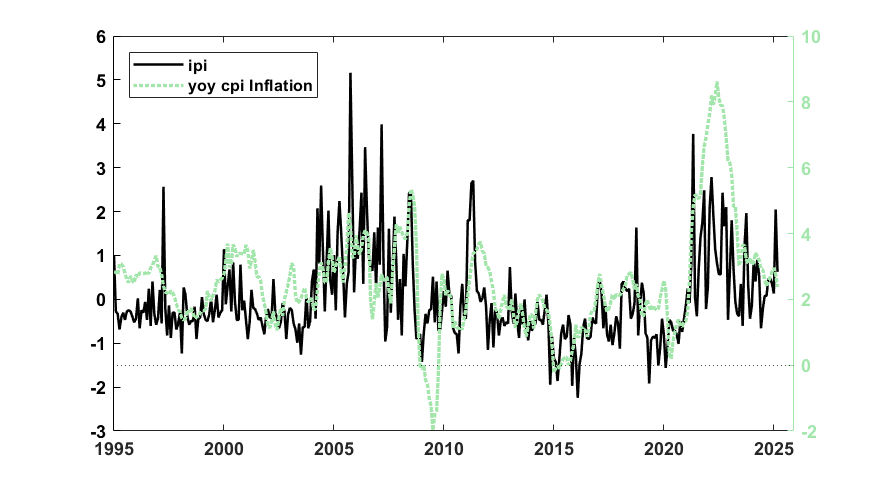

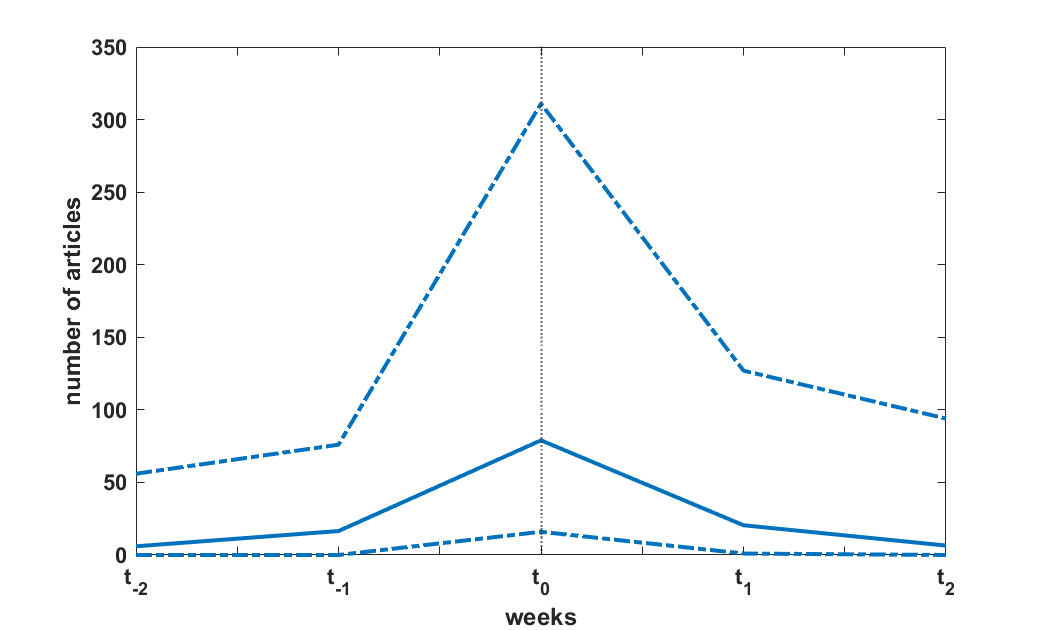

Using about 5,110 speeches by FOMC members and regional Fed presidents (1995 to 2025), the authors build an Inflationary Pressure Index (IPI) from speech text and ask a simple question: when Fed officials talk more about inflation pressure, do people update their expectations?

A Measurable Speech Signal

The index tracks inflation-related language in speeches, filters out backward-looking statements, and aggregates the remaining forward-looking tone.

The first result is clear: higher IPI is associated with higher one-year-ahead inflation expectations for both households and professional forecasters.

A one-standard-deviation increase in the IPI (roughly 50 additional inflation-pressure mentions in a month) is linked to:

- about +0.15 percentage points for households

- about +0.06 percentage points for professional forecasters

Delphic vs Odyssean Effects

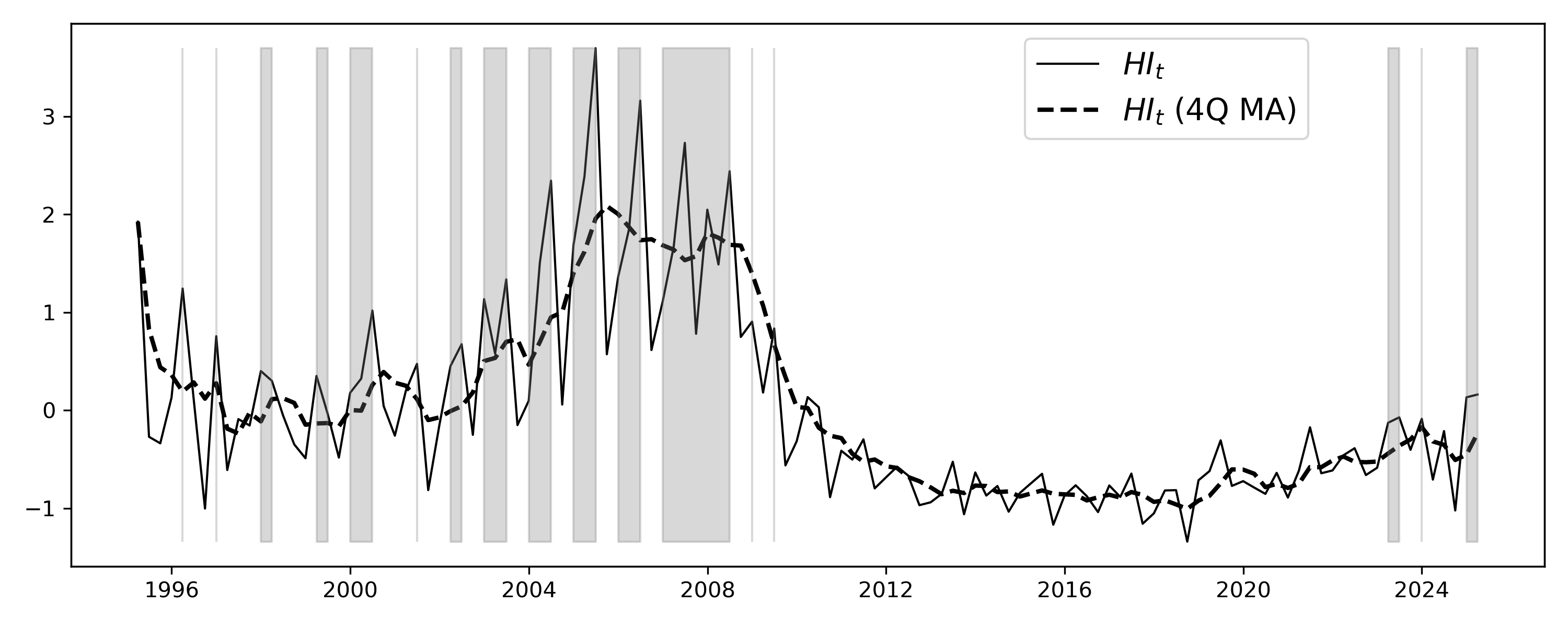

The paper separates two channels:

Delphic: the Fed reveals information about inflationary pressureOdyssean: the Fed signals how forcefully it will respond

To proxy the second channel, the authors construct a hawkishness index.

When inflation concerns are voiced by historically hawkish speakers, professional forecasters revise expectations down (or up less), consistent with an Odyssean interpretation. Households generally do not.

Why Households Still React

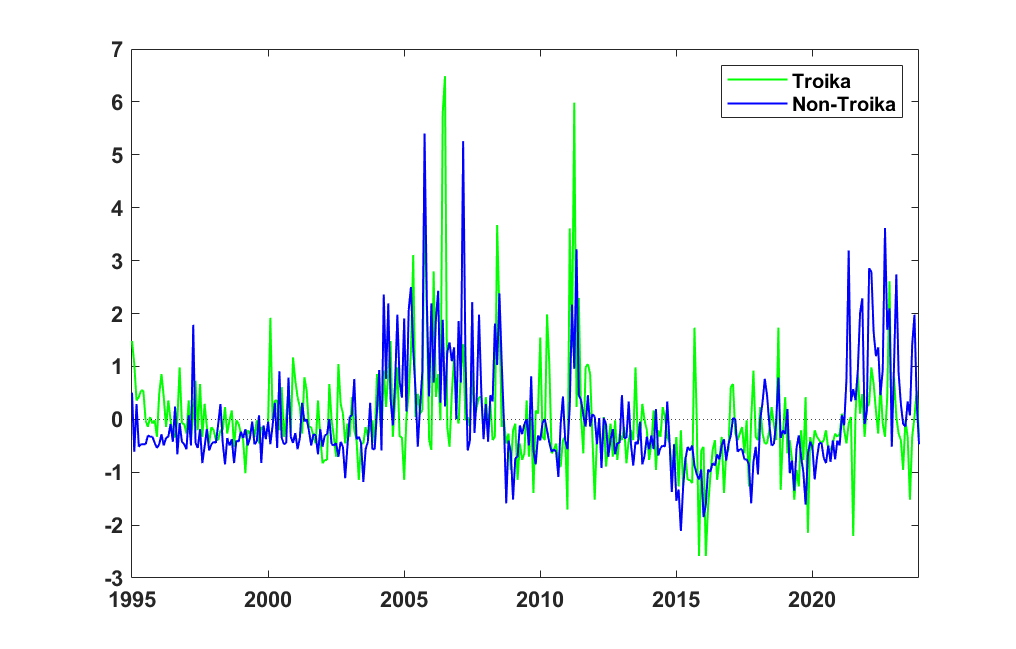

If households are less attentive to policy nuance, why do speeches still matter for them? The paper points to who is speaking and how messages are transmitted.

Households react more to communication by non-Trinity speakers (especially regional presidents), consistent with a regional-information channel.

The broader implication is practical: central bank communication is not one-size-fits-all. The same speech can raise expected inflation for one audience while anchoring expectations for another.

For policy, that means the message and the messenger both matter.